Chennai, like many Indian cities, once had a beautiful system for water management. When the water reached the maximum capacity in one lake, it cascaded into the next lake almost seamlessly. As a result of rapid and unplanned urbanisation, today these lakes carry raw sewage from one lake to another, flooding all the neighbourhood areas.

But on the bright side, quite a few communities have come forward to advocate for lake revival in Chennai. To equip the individuals and communities to conduct audits of urban lakes and hold authorities accountable, we organised a masterclass on September 20.

The session, facilitated by Shobana Radhakrishnan, Associate Editor with Citizen Matters, focused on two distinct but complementary parts in lake rejuvenation- the technical aspects of a waterbody and how to monitor lake quality, and the second part was about how citizens can take action towards lake rejuvenation.

Technical and hydrological understanding

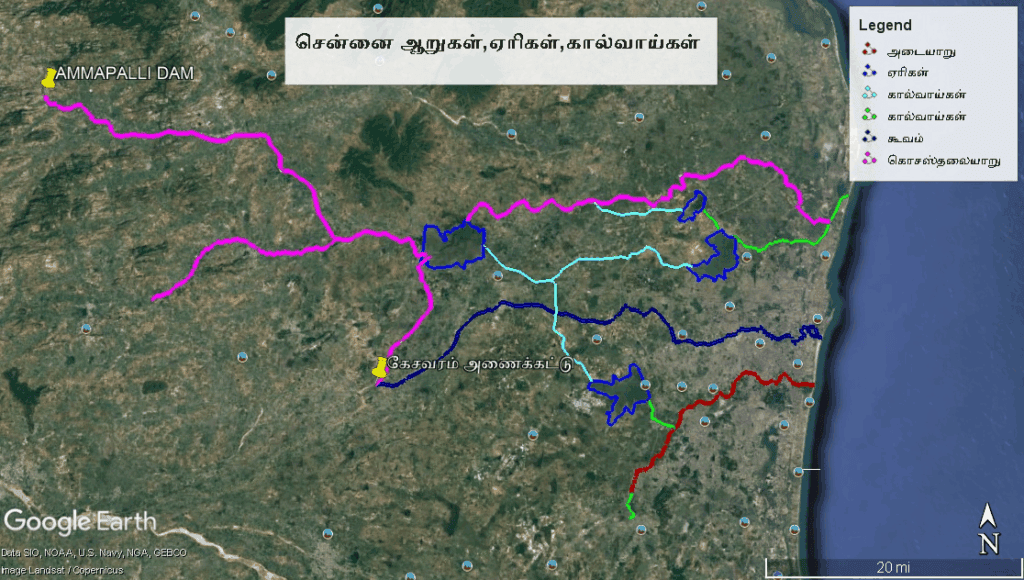

Shashank, senior hydrologist at WELL Labs covered the technical aspects of urban lakes. Noting that lakes in Southern India are rain-fed and function as interconnected tank systems, he highlighted that urbanisation modifies the natural water cycle by capturing and redirecting water and introducing pollutants.

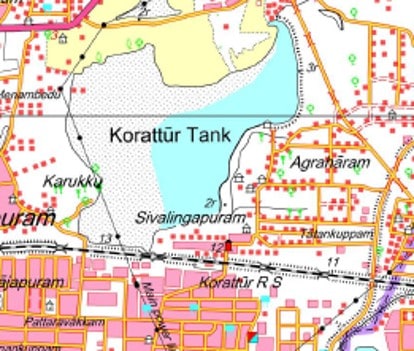

Shashank explained that identifying and assessing lakes involves looking at topographical sheets for guidance. In the above topo sheets shared by him, he pointed out blue patches on the sheets, which denote areas under water all year, and spotted black areas around them, which indicate the seasonal extent. He suggested using these boundaries as a reference.

He brought us to think about lakes as water bodies that serve multiple roles, including groundwater recharge, flood control, ecological support for biodiversity and the public spaces they provide. According to Shashank, the fundamental step in lake rejuvenation is establishing a “lake vision” in collaboration with stakeholders, government bodies, and the community. This vision could define primary functions, such as acting as a flood buffer or a recharge zone and some secondary and tertiary functions based on its location and water inlets.

He guided us to think of lake functionality being determined by three physical categories: hydrology (water quantity), chemistry (water quality), and biology (ecosystem health). He shared simple visual assessment checklists, focusing on features like inlets, outlets, bund strength, area of the recharge zone and pollution, for citizens to diagnose a lake’s current state.

Local context and accountability (Radhakrishnan)

Radhakrishnan of Arappor Iyakkam provided local context, stressing that water bodies are crucial as water cannot be created artificially.

He emphasised that the government is the “Guardian of the Water Body,” not the ‘Owner’, and has the sole responsibility for restoration, which often necessitates pressure from citizens.

Citizen audits, initiated after the 2015 Chennai floods (identified as a “man-made disaster”), found recurring causes: gradual increases in road height leading to residential flooding, lack of proper water body restoration, and poor connectivity between channels.

The neglect of water bodies results in reduced tank capacity, declining groundwater levels, and opportunities for corruption. He cited Pallikaranai Marsh as an example of significant degradation due to encroachment and use as a dumpsite.

Radhakrishnan provided practical methods for citizen engagement, including using tools like Google Earth Pro to determine elevation and water flow paths. Crucially, citizens can monitor government work by tracking tenders on the TN Tenders site (tntenders.gov.in). This allows citizens to verify if promised work, such as desilting, deepening, or bund strengthening, has been executed according to the tender specifications. This simple verification often reveals cases of non-performance or low-quality work.

He mentioned the successful legal effort to restore Villivakkam Lake, which had been filled with debris from the Chennai Metro Rail project, showing that data-backed court cases can force government action.

Citizen action and challenges

The speakers concurred that citizens collecting data in a systematic way is essential to ensure that authorities implement “environmentally and socially sensible designs” rather than centralised visions.

Participants raised questions about the conflicting national and state guidelines regarding buffer zones for lakes. For example, national disaster management guidelines suggest a 50-meter buffer for lakes over 10 hectares, while local authorities might approve setbacks as small as 3 meters, a difference often linked to powerful real estate lobbying.

The speakers concluded that to strengthen the connection between urban residents and water bodies, strategies like using simple water quality test kits, creating lake dashboards to explain water data, and organizing lake festivals for education and cultural engagement could be effective. They emphasized that sustained public involvement and holding the government accountable are essential, as official interest tends to fade soon after flood events.